Write your first custom policy

Writing a policy in Chainloop usually involvesGetting Started with Policy Development CLI Tools

Chainloop provides a complete set of CLI tools under thechainloop policy develop command to streamline your policy development workflow. These tools help you create, validate, and test policies locally before using them in your CI/CD pipelines.

Development Workflow Phases

-

Initialize your policy project - Start by generating a new policy using the

initcommand. This will create a new policy.yaml based on the Chainloop policy template. - Develop and refine your Rego logic - Within the generated policy.yaml, add Rego code tailored to your use case. You can begin with common patterns, then incrementally build more complex logic.

-

Validate syntax and structure early and often - Use the

lintcommand to detect issues. This ensures both the YAML structure and Rego code are valid, enforcing best practices via Open Policy Agent (OPA) and Regal. -

Evaluate policy logic with real inputs - Use sample SBOMs, attestations, or other artifacts to test your policy’s behavior with the

evalcommand. Violations or pass/fail results will be shown clearly, helping you quickly spot logic issues or edge cases. - Iterate and refine until policy behaves as expected - Use the feedback from eval to adjust your Rego rules. Re-run lint and eval until you’re confident in the policy behavior.

- Deploy to production - Once your policy is stable and validated, it’s ready to be versioned and rolled out into Chainloop and your CI/CD pipelines.

Example

Let’s walk through creating a policy that validates SBOM freshness: Step 1: Initialize the policy--embedded flag.

--debug flag for detailed evaluation output including input material with Chainloop context and raw evaluation results

In-Depth Policy Structure

Chainloop Policy YAML

A policy can be defined in a YAML document, like this:cyclonedx-licenses.yaml

- policies have a name (cyclonedx-licenses)

- they can be optionally applied to a specific type of material (check the documentation for the supported types). If no type is specified, a material name will need to be explicitly set in the contract, through selectors.

- they have a policy script that it’s evaluated against the material (in this case a CycloneDX SBOM report). Currently, only Rego language is supported.

- there can be multiple scripts, each associated with a different material type.

Supporting multiple material types

Policies can accept multiple material types. This is specially useful when a material can be specified in multiple format types, but from the user perspective, we still want to maintain one single policy. For example, this policy would check for vulnerabilities in SARIF, CycloneDX and CSAF formats:kind), the evaluation result will be the sum of all evaluations.

Policy arguments

Policies may accept arguments to customize its behavior. If defined, theinputs section, will be used by Chainloop to know with inputs arguments are supported by the policy

For example, this policy matches a “quality” score against a “threshold” argument:

- (1) the

inputsection tells Chainloop which parameters should be expected. If missing, the argument will be ignored (an no value will be passed to the policy) - (2) input parametes are available in the

input.argsrego input field.

threshold parameter, by adding a with property in the policy attachment in the contract:

to_number in the policy script

Writing Rego Policy Logic

Rego language, from Open Policy Agent initiative, has become the de-facto standard for writing software supply chain policies. It’s a rule-oriented language, suitable for non-programmers that want to communicate and enforce business and security requirements in their pipelines.Using Chainloop Template

Chainloop expects the rego scripts to expose a predefined set of rules. To simplify policy development, Chainloop automatically injects missing boilerplate rules.Injected code

result, if present

result object has essentially three fields:

skipped: whether the policy evaluation was skipped. This property would be set to true when the input, for whatever reason, cannot be evaluated (unexpected format, etc.). This property is useful to avoid false positives.skip_reason: if the policy evaluation was skipped, this property will contain some informative explanation of why this policy wasn’t evaluated.violations: will hold the list of policy violations for a given input. Note that in this case,skippedwill be setfalse, denoting that the input was evaluated against the policy, and it didn’t pass.

Template

valid_input and violations rules:

valid_inputwould fail if some preconditions were not met, like the input format.

Writing the policy logic

Let’s say we want to write a policy that checks our SBOM in CycloneDX format to match a specific version. Avalid_input rule would look like this:

violations rule would return the list of policy violations, given that valid_input evaluates to true. If we wanted the CycloneDX report to be version 1.5:

Attaching it to the policy YAML spec

Once we have our Rego logic for our policy, we can create a Chainloop policy like this:Contract Attachment

Once your policy is developed and tested, you can attach it to a contract:Configuring Policy Inputs

As we can see in the above examples, Rego policies will receive aninputs variable with all the payload to be evaluated. Chainloop will inject the evidence payload into that variable, for example a CycloneDX JSON document.

This way, input.specVersion will denote the version of the CycloneDX document.

Additionally, Chainloop will inject the following fields:

-

input.args: the list of arguments passed to the policy from the contract or the policy group. Each argument becomes a field in theargsinput:All arguments are passed asStringtype. So if you expect a numeric value you’ll need to convert it with theto_numberRego builtin. Also, for convenience, comma-separated values are parsed and injected as arrays, as in the above example. -

input.chainloop_metadata: This is an In-toto descriptor JSON representation of the evidence, which Chainloop generates and stores in the attestation. Developers can create policies that check for specific fields in this payload. A typicalchainloop_metadatafield will look like this:Besides the basic information (name, digest) of the evidence, theannotationsfield will contain some useful metadata gathered by Chainloop during the attestation process. The example above corresponds to an OCI HELM_CHART evidence, for which Chainloop is able to detect thenotarysignature. You can write, for example, a policy that validates that your assets are properly signed, like this:

Using Custom Evidence

In some cases, you might want to run a policy against a custom piece of evidence that doesn’t match any of the built-in material types.Structure Guidelines

We recommend that custom evidence has the following properties:- It’s in JSON format, since our policy engine only supports JSON.

- The document has an identifier, and clear separation between that and it’s actual data, for example

Troubleshooting

Common Issues

- Rego type conflicts: Remove

default violations := []when usingviolations contains msg ifrules - Missing material kind: Always specify

--kindparameter in eval command - Invalid JSON: Ensure your material files are valid JSON format

- Time calculations: Use nanoseconds for time comparisons in Rego policies

Debugging Tips

- Use

chainloop policy develop lint --formatto fix formatting issues - Test with minimal examples first, then add complexity

- Check the Rego Playground for syntax validation

- Use the CLI development workflow: init → lint → eval → iterate

- Add

print()statements in your Rego code for debugging - output is shown by default by eval command - Use the

--debugflag with eval command to see detailed input material and raw evaluation results

Performance Best Practices

- Minimize iterations: Use

someandcontainsefficiently - Early exits: Place most restrictive conditions first in rules

- Avoid deep nesting: Flatten complex object traversals where possible

- Cache calculations: Store expensive computations in variables

Policy Engine Constraints

To ensure the policy engine work as pure and as fast as possible, we have deactivated some of the OPA built-in functions. The following functions are not allowed in the policy scripts:opa.runtimerego.parse_moduletracehttp.send, by default is limited to the following hostnames:chainloop.devcisa.gov

Customize allowed hostnames

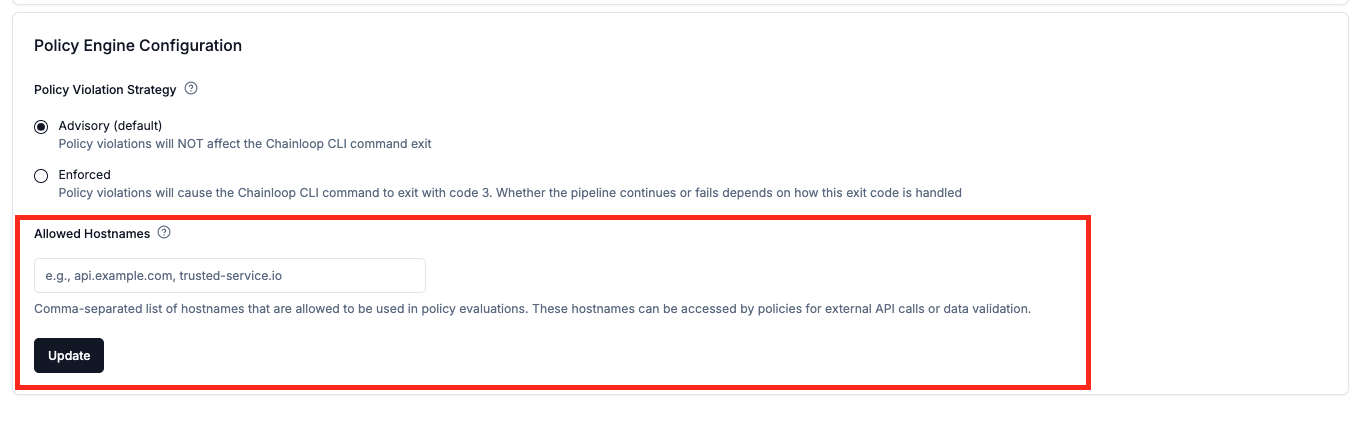

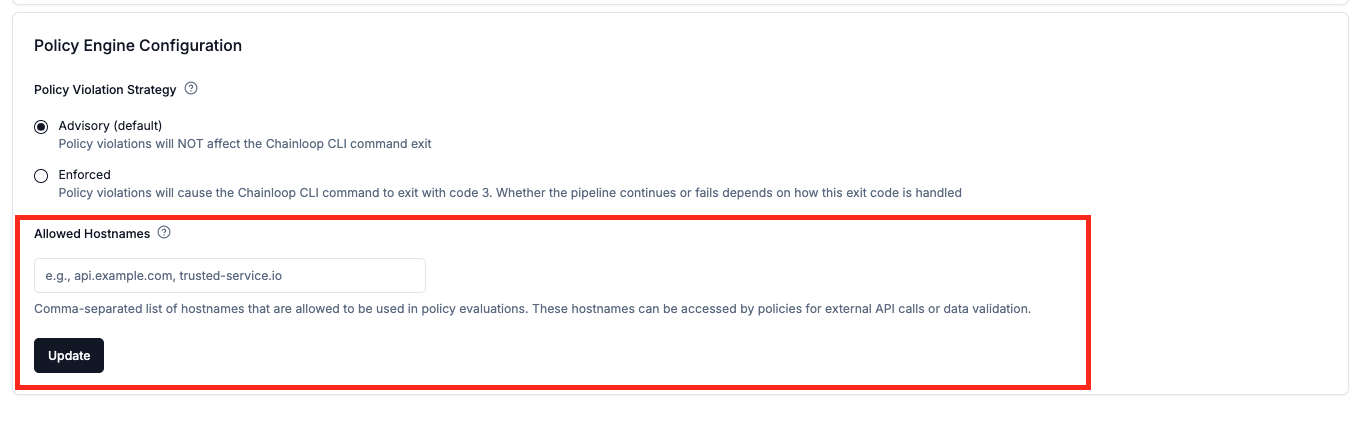

In some cases, you might want to allow the policy engine to make HTTP requests to additional hostnames, this can be configured through the organization settings.- Web UI

- CLI

Go to your organization settings and update the policy engine configuration.

Parameter and Evaluation Matchers

Chainloop supports custom auto-matcher Rego scipts that enable automatic policy matching for compliance frameworks. These matchers allow policies to define their own logic for determining compatibility with framework requirements, providing more sophisticated matching beyond simple parameter equality.Rego rules

matches_parameters

Used for automatic policy matching to determine if evaluation parameters are compatible with expected parameters from compliance frameworks.

Input:

input.args: The policy parameters provided during evaluationinput.expected_args: The expected parameters from the compliance framework requirements

matches_evaluation

Used for automatic policy matching to determine if evaluation results satisfy the compliance framework expectations.

Input:

input.expected_args: The expected policy parameters from the compliance framework requirementsinput.violations: Array of violation strings from the evaluation result

Example Usage

Consider a vulnerability policy that checks for security issues with different severity levels:matches_parameters: A compliance framework expects “high” severity vulnerabilities to be checked. A policy configured to check “medium” severity can satisfy this requirement (more restrictive requirement is acceptable), but a policy checking only “critical” severity cannot.

matches_evaluation: A compliance framework expects to detect “high” or higher severity vulnerabilities. An evaluation that found violations containing “critical” or “high” severities satisfies this requirement.

These matchers are implemented as Rego rules within your policy scripts and are automatically invoked during policy matching for compliance frameworks. When implementing these matchers, ensure they return boolean values and handle edge cases appropriately.

Example Rego Script

Here’s a simplified example of an auto-matcher script for vulnerability policies:Store Custom Policy

This feature is only available on Chainloop’s platform paid plans.

chainloop policy develop tools, you can store it in your Chainloop platform. The Enterprise Edition CLI provides policy management commands that let you manage policies directly from the command line.

Make sure you have the Enterprise Edition CLI installed. See the CLI Installation Guide for setup instructions.

ref property, just like built-in policies: